The VectorStorm Engine

People often ask about how I’m building MMORPG Tycoon 2. Is it built in Unity, or some other off-the-shelf engine?

Well, no. It’s built in a custom engine, one that I’ve been using for more than a decade. That engine is called VectorStorm, and is open source (You can find it on Github) It’s a classic, old-school style of game engine, written in plain C++. The kind of thing that I used at multiple companies in the game industry in the 90s and 2000s.

I don’t recommend custom game engines to most game developers today. So why am I using one? Well, that requires a bit of backstory.

Setting the scene

In 2006, I was working for Atari Melbourne House (née Beam Studios). I’d been with Melbourne House for almost ten years at that point, and had worked my way up to the position of Senior Programmer. I was, at the time, working as the network team lead on the PS2 version of Test Drive Unlimited; a game which Atari branded as a “Massively Open Online Racing” game. Basically, an MMO built around traditional racing tropes, rather than about traditional RPG tropes.

Toward the end of that project, Melbourne House was sold to another company; Krome Studios.

Shortly after the acquisition (after Test Drive Unlimited had shipped), Krome Studios started me on a new project which would go on to become the Wii version of Star Wars: The Force Unleashed, and sent me off to a Wii developer conference, to help bring me up to speed on the console. They gave me a huge box of business cards to take with me, to give to people at the conference.

(I don't seem to have given out very many of those cards)

N.B.: none of those contact details reach me any longer.

The important bit of that card is its second line: at Melbourne House, I had been a Senior Programmer, but immediately after the Krome purchase, my new business cards said that I was a Lead Programmer. I only found out about my promotion from these business cards; no one ever told me it had happened.

Needless to say, there was no pay rise associated with this stealth-promotion.

Also needless to say (at least, for those who know me well), the sudden promotion made me panic.

Yes, I’d been working at Melbourne House for nearly ten years at that point. Lots of people reach a ’lead programmer’ position a lot more quickly than that, but I still felt like a small fish in the big Melbourne House pond; there were lots of people there who were a lot smarter than me, and who had heaps more experience than me. I didn’t feel like I knew enough to be a proper lead, in that company.

A side-note: A lot of people (including me) believed that in the job title “Lead Programmer”, “Programmer” is a noun, and “Lead” is an adjective. That is, a “Lead Programmer” is a programmer who also leads. This is not correct.

In truth, “Lead” is the noun, and “Programmer” is the adjective. As a Lead Programmer, you are the leader who is in charge of the programmers. If you’re doing your job properly, you actually do little or no programming. Instead, the vast majority of your job is just managing the people who program.

This misunderstanding of mine, to some degree, explains the big mistake I was about to make.

Okay, back to the story.

Since I felt like I didn’t know all the details of how every part of a game worked, I did what almost nobody with any sense would do: I decided that the only way to make sure I could be an effective Lead Programmer was to build a complete game engine, from scratch, all by myself, in my spare time.

Yeah.

The game engine

Now, I wasn’t completely insane. I knew that I wasn’t going to write a commercial-quality game engine from scratch. And I wasn’t making the engine in order to create a game; I was just making the engine as a way to ensure that I learned the very basics of every field of game development.

I was going to write my own renderer, my own sound code, my own input handling code, my own physics, my own memory manager, my own file loading, and so on.

At about that time, I read an article about the hardware which ran Atari’s classic “Asteroids” coin-op game. In those cabinets, there was essentially one computer which ran the game, and an entirely separate computer that drew to the screen. The first computer would figure out what happened in the game, and would then generate a set of drawing commands (“Move cursor to position (x,y)”, “Draw a line to position (x,y)”), which got sent to the second computer. All the second computer did was to execute those commands; it didn’t know anything about the Asteroids game at all.

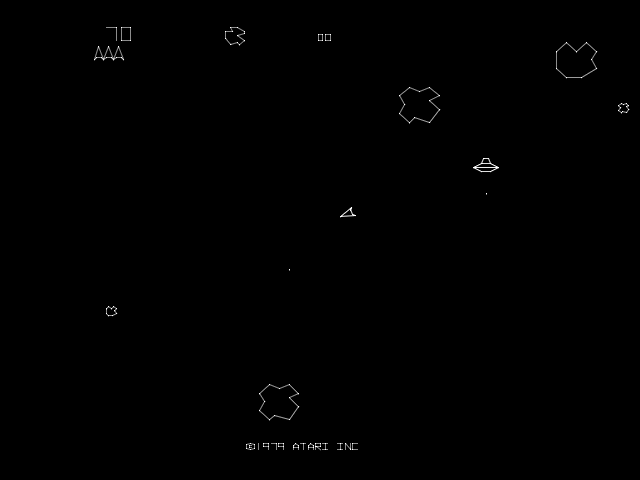

Atari's Asteroids

I thought that was a laughably complicated and entirely over-engineered way to handle rendering, and so I decided to mimick it exactly, in my engine’s renderer. Because it amused me to do something so absurd.

Like in Asteroids, a game written for my engine would construct a set of rendering commands each frame, which my renderer could then blindly execute without having to know anything about the game itself. I was greatly amused by the baroque design of this system.

VectorStorm Asteroids

It would be six years before I noticed that this “laughably complicated and over-engineered way to handle rendering” scheme was exactly the same thing being done in virtually every proprietary video game engine I had ever used in my career.

It turns out, it’s a standard practice. It’s generally acknowledged as being the optimal way to architect a game engine’s rendering components, in a really robust, high-quality rendering engine.

Unbeknownst to me, I’d implemented a completely viable and thoroughly non-absurd rendering system. And I’d done it completely by accident.

VectorStorm

A few years before this story, I was badly addicted to PopCap’s original Bejeweled.

I lost way too much time to this.

I was mostly a Linux user at the time (as I was a poor games industry person and computers were expensive, and Linux happened to run really well even on my ancient laptop). Since Bejeweled was only available on Windows and Mac computers, I couldn’t play it at home. So being a programmer, I built my own version of the game for Linux. As the game was about jewels that fell down from the top of the screen, I called that game “GemStorm”. (I had been unaware of the earlier DOS game also called “GemStorm” presumably for the same reason)

Now that I was creating a real game engine, I went back to my GemStorm game,

and took its source code to use as the basis for this new engine. As the new

engine was for vector graphic games and the old code was for a game I had

called “GemStorm”, I called the new engine “VectorStorm”. Some of that code is

still there in VectorStorm today; mostly in the vsScene, vsEntity, and

vsSprite classes.

Game-in-a-Week

As the VectorStorm engine progressed, I eventually wanted to prove its functionality to myself by building games that used it.

I was still a full-time employee in the mainstream games industry at the time, and I didn’t want my employers to get angry with me, so I decided to just design and construct very small games, and to release them for free. And I told myself that I wasn’t competing with my employers because these games were for the PC, while everything my employers did was for game consoles. (In truth, this was probably still a minor breach of my employment contracts)

To make this process more fun for myself, I challenged myself to design and implement each of these test games in a single week.

This is a much less surprising concept now than it was back then; these days we’re all used to game jams and other short-time-limit game development challenges. Back then, this sort of rapid game development was a pretty unusual thing.

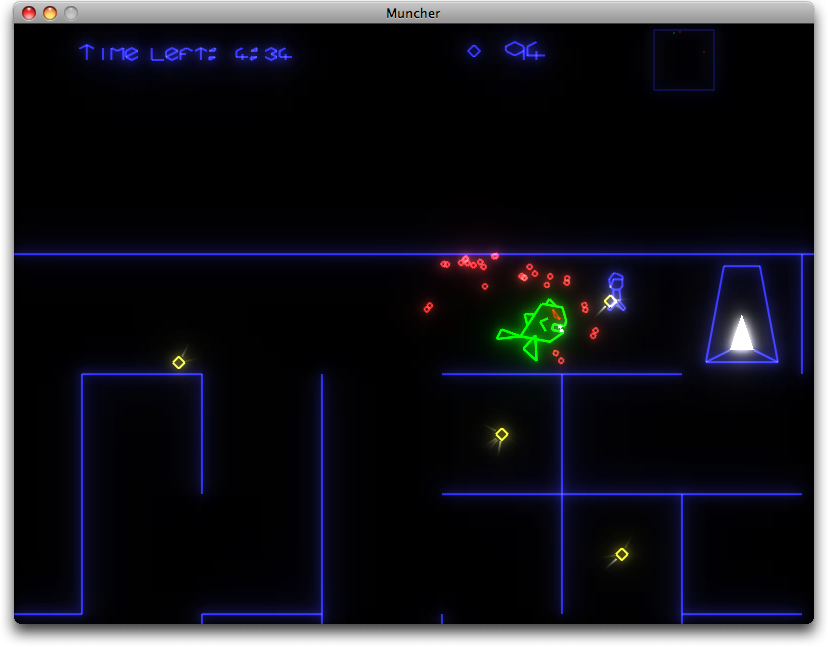

'The Muncher's Labyrinth', Game in a Week #2. This game added support for filled triangles in the VectorStorm engine

The “Game in a Week” games I made are still freely available on my old blog site. (I assume they all still work, but haven’t actually checked them in years!)

As time went on, the Game in a Week games encouraged me to add features to the VectorStorm engine. VectorStorm stopped being a “toy engine”, and started to be capable of making real, modern games. 3D was added, support for programmable shaders, and so on, as they were required for Game-in-a-Week games. Over the years, VectorStorm slowly began to look less and less like a “toy” game engine.

MMORPG Tycoon

In 2008, I created a little game called MMORPG Tycoon, as part of a game creation competition. I was feeling a bit disillusioned about the whole MMORPG genre, after having worked on Test Drive Unlimited, and having played a number of more classic MMORPGs, and so I wrote a little simulation to try to sort out my thoughts about what made people continue to play these games.

It seemed to me that fundamentally, you were just doing the same thing over and over again; moving from one place to another and grinding combat to make numbers go up. Why didn’t players get bored of that? MMORPG Tycoon was my attempt to explain the mechanics of what was going on to myself.

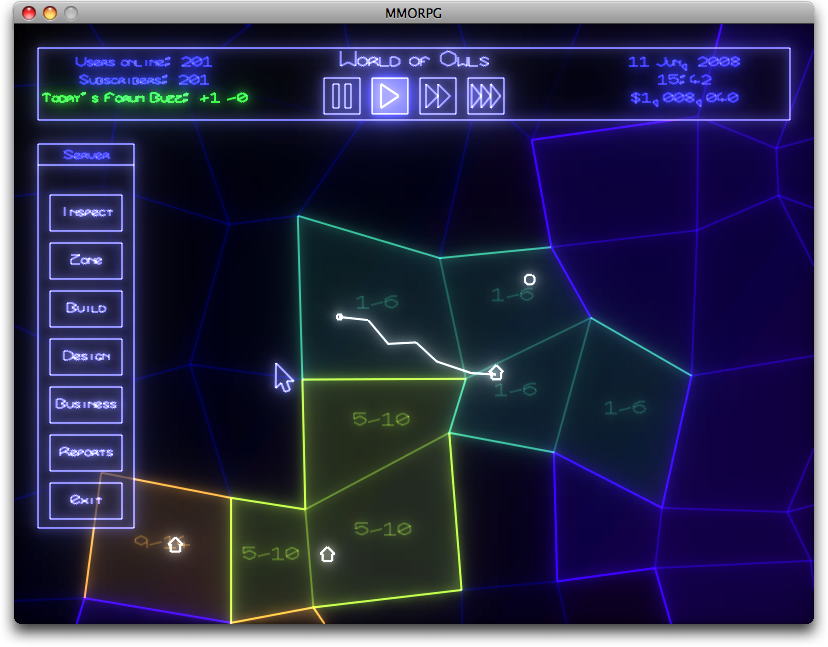

The map from the original MMORPG Tycoon

The game was fairly simplistic and abstract. And its simulation model wasn’t very rigorous. The game didn’t simulate quests or monsters at all; instead, players just wandered around at random, and the simulation just pretended that they encountered monsters sometimes, and would randomly subtract some health from players, to “simulate” combat.

But with that said, there was something slightly compelling about it. And the core game concept seemed to intrigue a lot of people. I always said that of all the games I’d made, this was the one that most seemed to ‘click’ with people. And it was the one that I most wanted to do a proper sequel to.

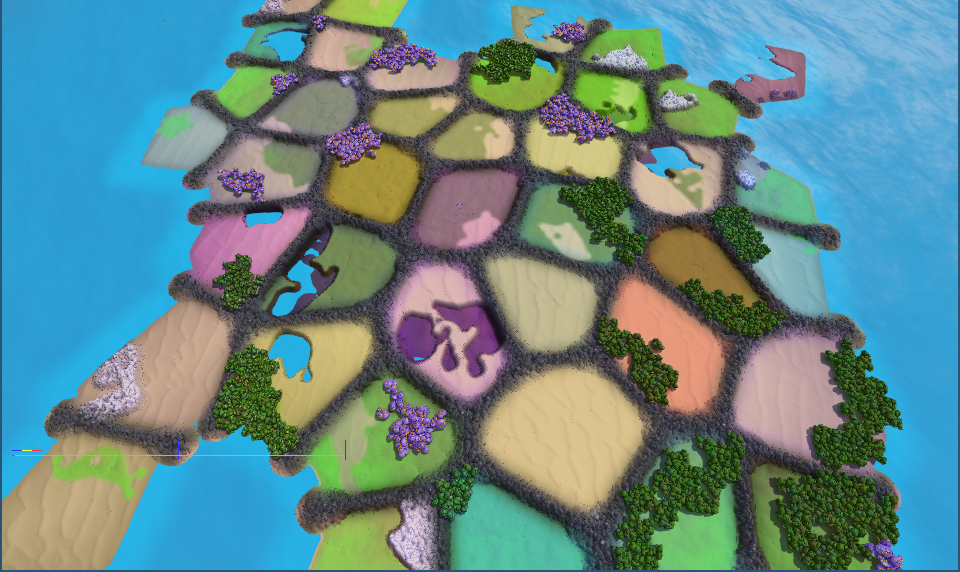

I’d always said that if I ever made an MMORPG Tycoon 2, it would run in full 3D; you’d be able to zoom the camera in and actually see the terrain, and see little character models playing the game and fighting monsters.

The Sequel

When I started building MMORPG Tycoon 2, I had two major concerns:

An empty map from the new MMORPG Tycoon 2

- In the original game, you could zoom out and see the whole game world all at once. I wanted to be able to do that in this new, 3D game as well. But there’s a lot more game geometry in a 3D game than in a 2D one. As just one example, there are potentially tens of thousands of trees all visible on screen at the same time, all of which have to cast shadows, and so on. So I needed an engine which could afford to render a lot of models really quickly.

- I had a whole MMORPG simulation from the original game written in C++ code, and I wanted to be able to reuse most of that simulation. Porting it all to another language or another framework would have been quite challenging!

At the time I began, Unity had just begun to be a thing, but it wasn’t nearly advanced enough yet to use the sort of hardware rendering features that I knew I was going to need. Unreal 4 wasn’t available yet, so it also wasn’t an option.

In the end, I went with my own, existing engine for MMORPG Tycoon 2 because I had it, I knew it, it worked, and the original game had been written using it. If I was starting from scratch today, I would likely go with Unreal or Unity.

But I’m pretty pleased with how it’s all been coming out! VectorStorm has done a pretty awesome job for me, thus far.